“Ralph”the Camarasaurus was collected in 2003 near the Little Snowy Mountains in Fergus County, Montana.

Camarasaurus lived in North America during the Morrison Formation (approximately 155-148 million years ago), meaning that this specimen is geologically, one of the oldest dinosaur fossils ever found in Montana. The Morrison Formation was home to some of our most classic dinosaurs: the meat-eating Allosaurus, the plated and spikey tailed Stegosaurus, and giant sauropods like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus. While some dinosaurs in the Morrison Formation are very rare (meaning we only have a few fossils to learn about that particular dinosaur), Camarasaurus is extremely common. To-date, over 175 Camarasaurus specimens are known in museums, making Camarasaurus the most common dinosaur in all of the Morrison Formation.

Oddly, in Montana, while we find Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Allosaurus, Stegosaurus (and it’s “cousin” Hesperosaurus) quite often, Camarasaurus is extremely rare. In fact, no Camarasaurus had ever been found in Montana before. Until “Ralph”. “Ralph” is the very first Camarasaurus ever found in Montana.

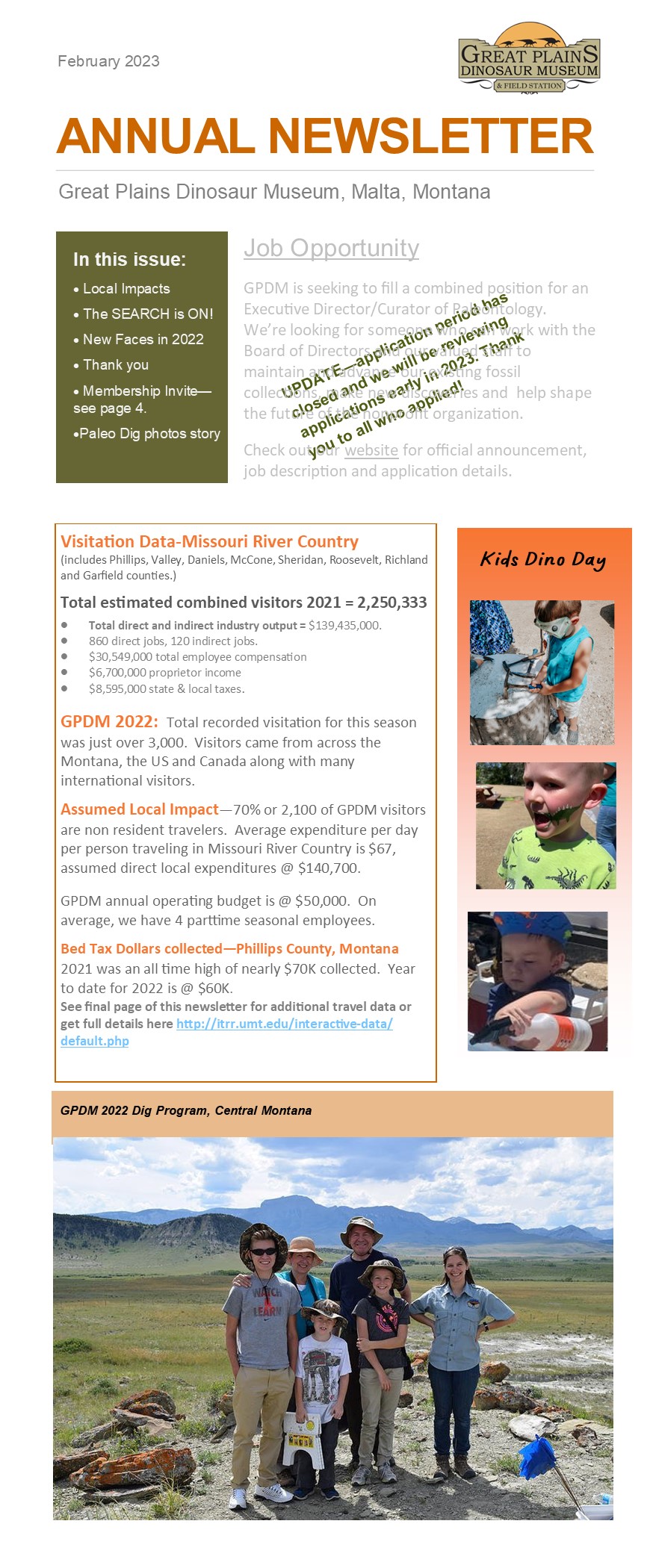

But surprisingly, when “Ralph” was found, it wasn’t recognized as a Camarasaurus. “Ralph” belongs to a group of dinosaurs called the sauropods (the long-necked dinosaurs), and the sauropods were the largest animals to ever live on land. While the bones of “Ralph” you see in the Museum look big, for a sauropod, and particularly for a Camarasaurus, they are not really that big. And while some of “Ralph’s” bones look very much like a regular Camarasaurus, other parts and features are a bit different. The people who found “Ralph” thought that it might be a new kind of sauropod. A team of paleontologists began to study “Ralph” in the summer of 2015 to try and solve this mystery. By looking at the bones of “Ralph” and comparing them to all other sauropods from the Morrison Formation, and looking at the microscopic anatomy from the inside of the bones, the paleontologists determined that “Ralph” really was a Camarasaurus. But what about the odd looking parts and the small size of “Ralph”? Sauropods were the largest animals ever to walk the Earth, meaning that the bigger you are, the more your bones have to be designed and shaped differently to deal with your giant size. “Ralph’s” bones are shaped a bit differently from a larger, typical Camarasaurus, just because “Ralph” didn’t grow up to be as big – it’s bone’s didn’t have to be shaped and designed like a big Camarasaurus.

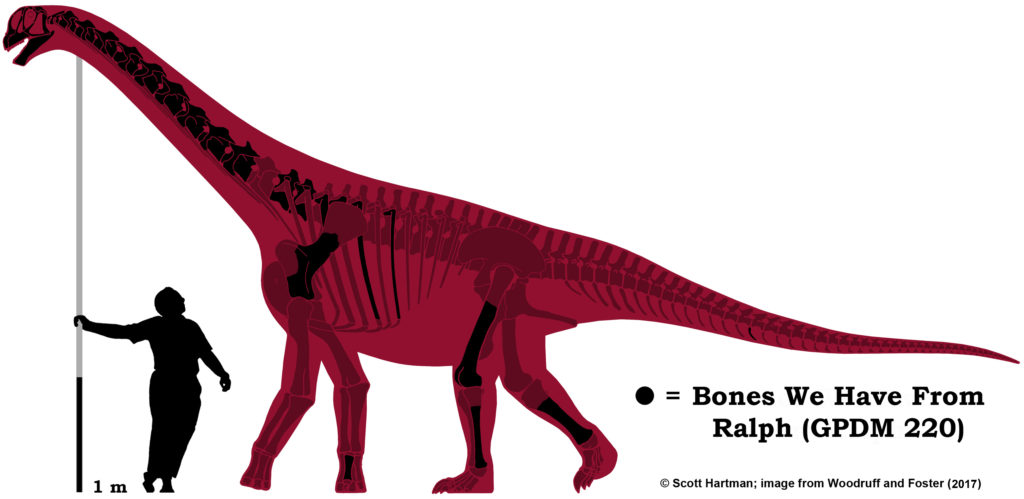

Also, the inside of “Ralph’s” bone revealed some fascinating information. A long time ago, paleontologists used to think that the size of an animal correlated to its age: small dinosaurs must be young, big ones must be old. We see this trend today; babies are small because they are very young, and adults are bigger because they have grown up. But size and age are not a strict rule. In your own school class, different boys and girls may have similar ages, but heights can vary. And just because a super tall professional basketball player is taller than you does not mean that they are some of the oldest people on the planet. And the same is true for dinosaurs. By looking at the inside of “Ralph’s” bones and counting growth rings (just like counting rings in a tree to determine its age), the paleontologists determined that “Ralph” was approximately 30 -35 years old when it died. That may not sound very old, but “Ralph” is in fact one of the oldest (meaning how old it was when it died) dinosaurs that we know of!

So the bones of “Ralph” look a bit different because it was a small, old Camarasaurus. This may not sound as interesting as a new species, but for paleontologists this is super important. Understanding the kinds of variation and the life history (how it grew up) help us understand and answer way more questions about that particular kind of dinosaur.

But why is Camarasaurus so rare in Montana? We haven’t been able to answer that particular question yet. Maybe it’s a sampling bias – if we do more collecting in the Morrison Formation in Montana, perhaps we’ll start finding more. Maybe Camarasaurus didn’t eat the plants that plants that grew in ancient Montana. Maybe Camarasaurus couldn’t compete with the other dinosaurs here in Montana. We don’t know these answers, and that’s okay. Maybe one day a future paleontologist will solve this riddle. And “Ralph” will help answer these questions.

Check out the scientific research done on “Ralph”!